Are Microplastics in My Drinking Water? The Ultimate Guide

Our blog is written by real experts— not AI. Each guide is carefully reviewed and updated based on the latest research. Plus, with no affiliate links, you can count on unbiased insights you can trust.

Microplastics are tiny plastic particles that are invisible to the naked eye, but they’ve been found in tap water, bottled water, and even rain. In this ultimate guide, we’ll explain where microplastics come from, how they may affect your health, and what you can do to detect and remove them from your drinking water. We also cover the latest research, EPA regulations, and expert answers to common questions.

Table of Contents:

- What Are Microplastics?

- Where Do Microplastics Come from?

- Do Microplastics Impact Human Health?

- Does the EPA Regulate Microplastics?

- How Do You Know if You Have Microplastics in Drinking Water?

- Can You Test for Microplastics?

- How Do You Filter Microplastics from Drinking Water?

- Common Question and Concerns

- What’s the Takeaway?

What Are Microplastics?

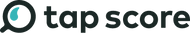

Microplastics are tiny plastic particles, technically defined as larger than 1 micron (1 μm) and smaller than five millimeters (5 mm) in diameter. Five millimeters is about the size of a sesame seed, though microplastics can be smaller than the period at the end of this sentence.

1mm (millimeter) = 1,000 µm (micron, also known as micrometers)

What Are Nanoplastics?

Nanoplastics are plastic particles that have degraded to less than 1 µm. That’s in the realm of bacteria (~2 µm), and smaller than the average red blood cell (~6-7 µm). This size difference affects their interaction with the environment and potential toxicity.

Nanoplastics in the environment likely derive from microplastics that have broken down to the even smaller “nano” size category.

Are PFAS Microplastics?

No, PFAS — per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances — are not microplastics.

Both PFAS and microplastics are emerging human-made contaminants of environmental concern. PFAS contain thousands of different compounds that can be loosely defined by their structures, which have multiple fluorine atoms bonded to an alkyl chain. They are largely used in non-stick or water resistant products like frying pans, jackets, and food packaging.

Microplastics are also a complex class of chemicals, but their chemical composition is distinct. Plastics are technically polymers, and they have many applications due to their ability to be shaped when soft and then retain a shape when hardened.

Learn more: Ultimate Guide to PFAS in Drinking Water

Where Do Microplastics Come from?

Microplastics come from a wide variety of sources because plastic is such a major part of our world. They have been detected extensively in sea water, surface waters and drinking water (including tap water and bottled water) around the globe.

Primary vs Secondary Microplastics

Primary microplastics are intentionally manufactured microplastics, used in commercial products, such as in cosmetics. They include:

- Microbeads, found in face washes and toothpaste

- Nurdles, or small plastic pellets used for manufacturing plastic

Secondary microplastics are created indirectly as larger plastics break down through physical, chemical, and biological processes. These tiny pieces of plastic include:

- Stray bits of synthetic fiber from laundered clothes

- Synthetic particles

- Fragments from the disintegration of plastic waste

- Films

- Foams

Are There Microplastics in Bottled Water?

Most likely. While not every bottled water brand has been tested, research shows that concentrations of microplastics in water bottles made of plastic are higher than in tap water.

How Do Microplastics Affect Human Health?

As microplastics are a relatively new field of study, the effects of microplastics on human health remain largely unknown. At the moment, both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) have stated there is insufficient evidence linking microplastics to concrete health effects.

Are there Potential Microplastics Health Risks?

Aside from the physical hazards of ingestion, microplastics carry the health risks associated with plastics more generally, such as leaching (plastics have the ability to absorb toxic chemicals and to leach them out). Additionally, microplastics themselves can foster the formation or growth of biofilms in distribution systems (which could include harmful pathogens).

Research into microplastics is ongoing. Key areas of discovery include the impact of microplastic exposures depending on their size and material. We’ll cover this in more detail below, but suffice it to say there is less cause for alarm than you might think.

Are Microplastics Regulated?

In the United States, microplastics remain largely unregulated. The only piece of legislation in the field of microplastics is 2015’s Microbead-Free Waters Act. Congress amended the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FD&C) to prohibit the manufacturing, packaging, and distribution of rinse-off cosmetics containing plastic microbeads. This includes cosmetics and OTC (over-the-counter) drugs, such as toothpastes.

Individual states are free to pursue their own legislation. But regulation tends to follow behind research by many years, and as mentioned, microplastics are only recently taking off as a field of study.

How Do You Know if You Have Microplastics in Your Drinking Water?

Microplastics that have entered a water system and made it through a treatment plant to your tap cannot be seen, smelled or tasted. The only way to know if microplastics are in your drinking water is to invest in a microplastics water test with a certified laboratory.

How Do Microplastics Get into Drinking Water Systems?

Microplastics get into our drinking water in a few different ways. Water carrying plastics from used products or other trash eventually leads to water sources like rivers, lakes, and reservoirs. Other ways include plastic breaking down directly in the environment, overflow from sewers, particles from the air, and liquid waste from factories and heavy industry.

Does Your Water System Make a Difference?

Microplastics are an issue that affects both public water systems and private wells. Microplastic contamination has reached groundwater and surface water sources—like aquifers, rivers, and lakes—that impact both wells and utilities.

Water treatment facilities use a variety of treatment technologies, and conventional treatment does remove microplastics to some degree. Removal efficiencies vary substantially, however.

It’s generally understood that conventional drinking water treatment is not very effective at removing smaller microplastics.

Can You Test for Microplastics?

Yes, but only through a certified lab. There are no at-home tests currently available that can identify the presence of microplastics in a sample of water.

How to Test Water for Microplastics

Testing for microplastics is as simple as collecting a water sample from your faucet and sending it out for analysis. Your test will specify which sampling method is required, but a fully-flushed sample—which is where you run your water for a few minutes to flush your plumbing system to clear out any contaminant buildup from your pipes—is typically called for to shed light on the quality of your water supply, rather than your plumbing.

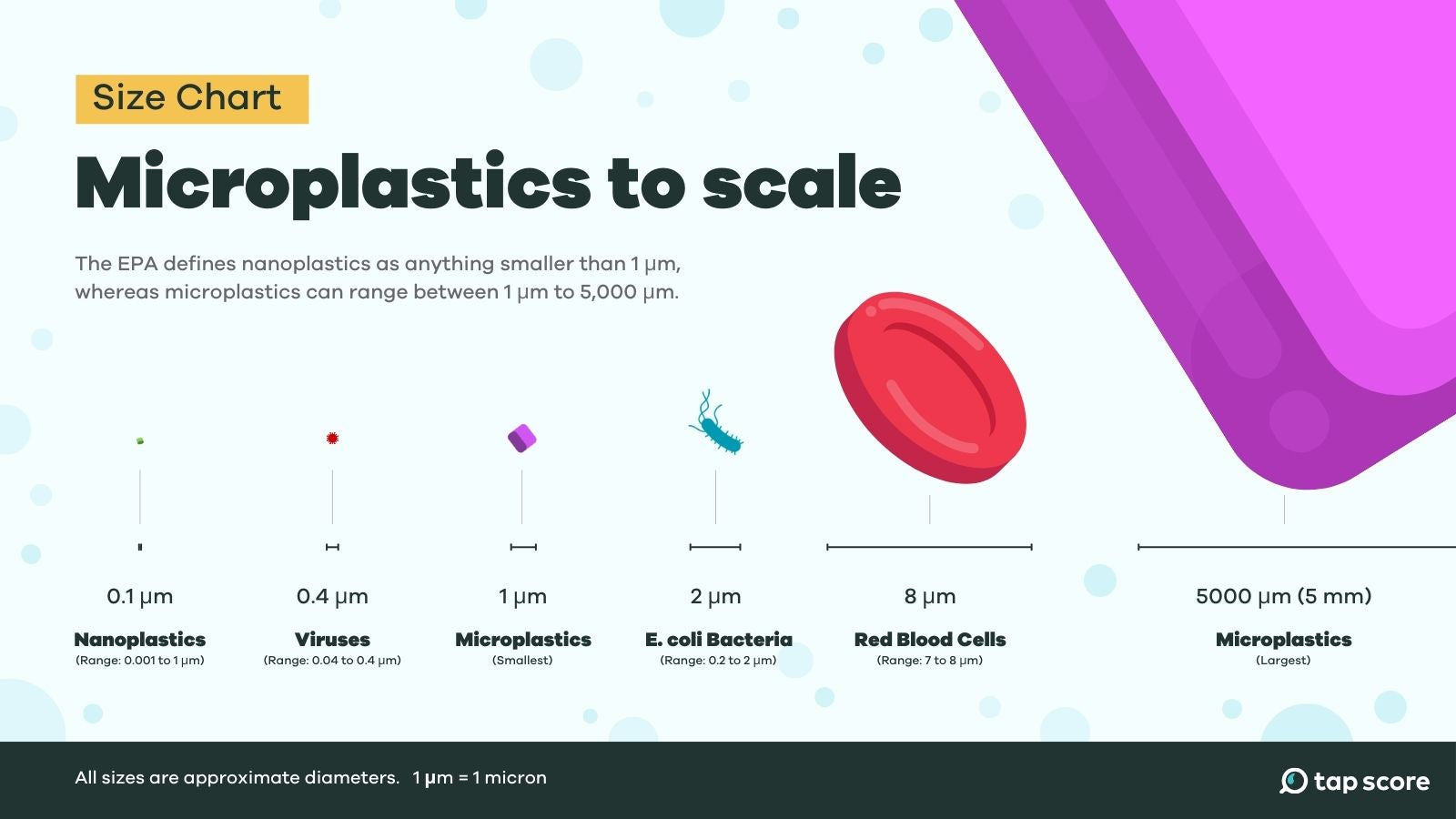

How Are Microplastics Tested?

When you purchase our microplastics water test kits, our certified lab partners will use a combination of optical microscopy, polarized light microscopy, and Raman spectroscopy to detect microplastics as small as 1 µm.

Raman spectroscopy refers to a spectroscopic technique which involves the changes of monochromatic (laser) light as it interacts with a sample of interest. The Advanced Microplastics Water Test Kit breaks microplastics down by size category and polymer type allowing for accurate identification of the specific type or types of plastic in the sample.

Note: Because microplastic analysis is still an emerging field without standardized laboratory protocols, there is not one single standard method or technique that works well for all labs. More details about microplastic testing methods are forthcoming.

Can You Test for Nanoplastics?

No, methods to accurately identify nanoplastics (< 1 μm in size) are not yet available to the public. Both the methods and instruments required for a satisfactory nanoplastics water test are highly specialized and largely under development in academic labs.

Should I Be Concerned About Microplastics and Nanoplastics?

As with all “contaminants of emerging concern,” there is a valid reason to be mindful of the potential impacts of micro- and nanoplastics on your health and the environment. But concern is not necessarily cause for alarm.

Although there isn’t enough evidence from a health perspective to ring the alarm bells just yet, staying informed about the latest scientific developments is a wise approach. Beginning with a thorough understanding of your overall water quality is a great place to start.

Contaminants like heavy metals, disinfection byproducts, PFAS, and volatile organic compounds (VOCS) have years of research and proven studies into their sources and treatment options. Prioritizing what you can exercise control over will go a long way toward improving the overall toxicity risk of your water.

Not sure where to get started? Water testing kits — like Tap Score’s Advanced City and Well tests — offer analysis of over 100 contaminants. They also include treatment recommendations for your unique water profile.

By focusing on a broader array of contaminants, you can learn a lot about your overall water quality while finding recommendations for a treatment technology that’s also effective at removing microplastics.

How Do You Remove Microplastics from Your Drinking Water?

Current studies show that best filters for removing microplastics from your drinking water utilize membrane filtration. You'll want to pay attention to certifications, though, to help ensure your treatment device can effectively reduce microplastics.

NSF/ANSI certification 401 requires a filter to reduce microplastics of about ≥ 0.5 µm to < 1 µm in size by at least 85 % when operated. However, many filters are actually more efficient. This means there are already off-the-shelf systems for home tap water treatment that can provide adequate protection from microplastics.

When selecting a water filtration technology, you should ensure the filter’s packaging says it is certified under NSF/ANSI standard 401 for the removal of microplastics. Look for the NSF/ANSI seal, or one from WQA or IAPMO. You can also check the filter pore size. Pore sizes of 2.5 µm or less should filter microplastics from your tap water effectively, although it’s worth mentioning there is no one-size-fits-all, best water filter for microplastics.

Ultimate and Unbiased Guide to the Best Water Filters for Your Home

Does Reverse Osmosis (RO) Remove Microplastics?

Yes, reverse osmosis (RO) should effectively remove all or nearly all microplastics. RO works by using high pressure to push water through a semipermeable membrane with very small pores; the pores allow water to pass through but keep many contaminants from doing so.

Note: RO systems use more energy and water than other treatment methods, and they produce a waste stream.

Does Nanofiltration (NF) Remove Microplastics?

Micro-, ultra-, and nanofiltration will remove the majority of microplastics. Specifically, microfiltration rejects particles >1 µm, ultrafiltration rejects particles >0.01 µm, and nanofiltration >0.001 µm.

Does Activated Carbon Filter Microplastics?

Some activated carbon filters can remove microplastics. But to be certain, make sure you only consider filters that are certified to reduce microplastics.

Does Brita Filter Microplastics?

Yes, the Brita Elite Filter is certified under NSF/ANSI 401 to reduce microplastics. However, the Standard Brita pitcher filter is not certified for microplastics reduction.

What Do Brita Pitchers Filter Out?

Does Berkey Filter Microplastics?

There isn’t a straightforward answer to this. Berkeys are an interesting case because — despite the host of claims touting their near total effectiveness — no one except Berkey really knows what their proprietary filter media (Black Berkey Elements) are made of.

While we would feel more comfortable knowing the pore size of Berkey’s filtration membrane, many of the contaminants Berkeys appear to be effective at removing (like certain heavy metals and microorganisms) are smaller than microplastics. This would theoretically make Berkeys effective for the removal of microplastics.

Nevertheless, without any proper certification from the WQA, IAPMO, or NSF/ANSI for the removal of microplastics, we can’t recommend Berkey water filters for your microplastic filtration needs.

What Do Berkey Pitchers Filter Out?

Does Boiling Water Remove Microplastics?

No, boiling water does not remove microplastics. Boiling water is only effective against pathogens and bacteria. Boiling water will not eliminate the small plastic particles/polymers that are microplastics.

It’s also important to note that there are a number of contaminants that concentrate when boiled, posing different health risks. Also, if you are boiling water inside of a plastic container, like a plastic kettle or plastic bottle, it is possible that this will release microplastics from the container into your water.

Frequently Asked Questions About Microplastics and Storage Containers

Can Water Filters with Plastic Housing (incl. Pitcher Filters) Leach Microplastics into Drinking Water?

There is no substantial research into water filters or their plastic housing leaching microplastics into drinking water. But, it’s probably a safe bet that microplastic leaching from a durable plastic housing would be insignificant.

Pitcher filters made of plastic, on the other hand, are often used for years and may degrade over time. Over a long period of time, plastic leaching may occur, but more research into this area is needed to fully understand the risks.

Is it Safe to Use Reusable Water Bottles Made of Plastic? Of Glass?

Theoretically, any product made of plastic can leach microplastics if it’s subjected to regular, repeated use. The quality and type of the bottle’s plastic contributes as well. Certain environmental factors (e.g. temperature, direct sunlight) can also cause physical, chemical, or biological degradation. Even the plastic lid of a water bottle — whether the bottle itself is made of plastic, glass, or aluminum — used at high frequency is liable to contribute to microplastic combination.

Glass or other non-plastic containers themselves would not contribute to microplastic leaching. But remember, the source of the water you are storing could have microplastics in them.

What About Other Foods and Drinks Stored in Plastic? Can They Contain Microplastics?

Yes, food and drink stored in plastic containers can be contaminated with microplastics if their plastic containers are of low quality (like single-use plastics), repeatedly used, and/or subject to the type of factors that can accelerate degradation.

Reheating food in plastic containers, for example, may pose a risk because microplastic leaching is highly temperature-sensitive.

If Microplastics Are Bad, Why Are Filters Made Out of Plastic?

Plastic has long been prized for its low price and versatility. Most products are made from plastic because of plastic’s moldability. However, your specific filtration setup may not be contributing a significant amount of microplastics to your drinking water.

Importantly, as mentioned, studies in this area are ongoing. The best thing you can do is store your plastic pitcher filters and containers away from sunlight, and, if they are subject to a lot of wear and tear, replace them.

What’s the Takeaway?

Microplastics certainly are here, and they are here to stay. But that doesn’t mean they’re worth all of your attention.

- Microplastics are tiny plastic particles, between one micron (1 μm) and five millimeters (5 mm) in diameter; nanoplastics are plastic particles that have degraded to less than 1 µm.

- Microplastics that have made it to your tap cannot be seen, smelled or tasted. The same is true for microplastics in bottled water. The only way to know if microplastics are in your drinking water is to have your water tested by a certified laboratory.

- There are no at-home testing options (like strips) that can identify the presence of microplastics in a sample of water.

- Current studies show that microplastics can be removed by household drinking water treatment technologies like reverse osmosis, micro- ultra- and nanofiltration, and certified activated carbon filters. Boiling water does not remove microplastics.

- Systems certified to NSF/ANSI 401 specifically for microplastics are the best picks against microplastics.

Read More

▾PFAS in Drinking Water: Everything You Need To Know

What Do Brita Pitchers Filter Out?

Bottled Water: Myths vs. Facts

Berkey Water Filters: An In-Depth Analysis of Performance and Certification

Ultimate and Unbiased Guide to the Best Water Filters for Your Home in 2026

Sources and References

▾- EPA Microplastics Research

- WHO Health Risks of Microplastics

- WHO Microplastics in Drinking Water

- CDC & ATSDR Review of Health Data on Microplastics

- Microplastics in drinking-water | World Health Organization

- Microbead-free Waters Act—FAQs | FDA

- Drinking Boiled Tap Water Reduces Human Intake of Nanoplastics and Microplastics | Environmental Science & Technology Letters