Quick Guide: Chlorine and Chloramine in Drinking Water

Our blog is written by real experts— not AI. Each guide is carefully reviewed and updated based on the latest research. Plus, with no affiliate links, you can count on unbiased insights you can trust.

Our drinking water is sourced from rivers, streams, lakes—waterways which are all subject to waterborne pathogens. Water treatment facilities use chlorine and chloramine as disinfectants to help protect us against illness.

But what separates chlorine and chloramine as disinfectants? In this guide to chlorination and chloramination, we’ll take a closer look at water disinfection, spotlighting its benefits, its hazards, and what it all means when it comes to your health.

Table of Contents:

- What Is Water Chlorination?

- Is Chloramine the Same as Chlorine?

- Risks Associated with Chlorine in Drinking Water

- Is Water Disinfection Regulated?

- Filtering Water for Chlorine and Chloramine

- Testing Water for Chlorine and Chloramine at Home

- What’s the Takeaway?

What Is Water Chlorination?

Water chlorination is a common method used to disinfect drinking water by adding chlorine (as a gas or as hypochlorite liquid or solid) to it. Chlorine is highly effective at killing harmful coliform bacteria, like E. coli, viruses, and other microorganisms that may be present in water sources and cause illness.

Chlorine was first introduced into water systems in the United States in 1908, in Jersey City, New Jersey to help make water safer for daily human consumption. Federal regulation of water quality began in 1914 when the US Health Service set standards for bacterial content in water. Chloramine, on the other hand, was first introduced to water systems in the US in Cleveland, Ohio, Springfield, Illinois, and Lansing, Michigan in 1929.

Why Is Water Chlorination Important?

In the United States, effective disinfection of drinking water by chlorination (and chloramination) has helped eradicate formerly widespread waterborne diseases including:

- Cholera

- Typhoid fever

- Dysentery

It has also minimized the risks associated with a variety of other diseases caused by microorganisms in drinking water, including hepatitis and giardiasis.

How Does Water Chlorination Work?

Water chlorination involves adding chlorine gas, liquid chlorine, or solid chlorine compounds to a water supply before it leaves the treatment plant. Water treatment facilities (like your local public water utility) carefully control and adjust concentrations of chlorine for proper disinfection.

Once added, chlorine reacts with organic matter and microorganisms that broke through earlier treatment steps or that are introduced in the distribution lines. Chlorine disinfection effectively neutralizes them and prevents the spread of waterborne diseases.

Do alternative methods of drinking water disinfection exist?

Yes, alternative methods of drinking water disinfection exist—including ozonation and UV radiation which are popular in Europe. But chlorine is still the most common disinfectant used to treat water in the US.[1] Unlike ozonation and UV radiation which do not add a residual, chlorination affects the flavor and odor of treated water.

When Is Drinking Water Chlorinated?

For the purposes of disinfection, water chlorination occurs as the final step after water has been treated and filtered to remove other contaminants. This step is called “primary disinfection”.

Chlorine is often added again after primary disinfection, referred to as i.e. "secondary disinfection", so that it remains as a "residual" in the water as it travels through the distribution line to customers. When added to create a residual, chlorine is effective earlier in the distribution line, with a risk of dissipation relatively quickly.

Water systems work at the treatment plant to maintain the chlorine levels throughout the water distribution system.

Free Chlorine vs. Total Chlorine

- Free chlorine is the amount of chlorine available to disinfect your water.

- Total chlorine is the sum of free chlorine and combined chlorine, or the chlorine that has combined with contaminants and their byproducts during the disinfection process.

Is there a difference between chlorine and fluoride?

Chlorination and fluoridation are not related apart from the fact that they are both processes public utilities use to protect public health.

Fluoride, an inorganic compound formed from the reaction of the fluorine element with minerals in rock and soil, is added to tap water systems in a process called fluoridation to help prevent tooth decay by strengthening the enamel of teeth.

Chloride, on the other hand, is a compound or molecule with chlorine in it (e.g., sodium chloride—table salt).

Is Chloramine the Same as Chlorine?

Not exactly. Chloramines are compounds that contain a combination of chlorine and ammonia. One in five Americans uses water treated with chloramines. Monochloramine, referred to simply as chloramine, is the type of chloramine used in water disinfection.

Chloramine is a weaker disinfectant than chlorine, needing both a higher concentration and a longer contact time to disinfect compared to chlorine. It is, however, more persistent. As such, water treatment facilities can maintain better residual levels of monochloramine after it leaves the water treatment plant for continued purification throughout the distribution system. This ensures that the water remains safe to drink as it travels from the treatment facility to your tap.

What Are the Side Effects of Chlorine in Drinking Water?

Water chlorination and chloramination are associated with a number of health risks or possible side effects. Nevertheless, the consensus remains that the risks associated with chlorine (and chloramine) disinfection are offset by its benefits.

Disinfection Byproducts (DBPs)

Scientists began to discover that chlorination, while effective at inactivating harmful pathogens, had the unintended consequence of generating byproducts like trihalomethanes (THMs) and haloacetic acids (e.g. HAA5/HAA9) when natural organic matter levels in the source water are high.

A number of DBPs have the potential to cause negative long-term health effects, including increased risk of cancers and reproductive issues. The EPA introduced regulations for DBPs in 1998 and further expanded them in 2006—though these regulations cover a small fraction of the known DBPs in our drinking water.

Formation of regulated DBPs like THMs is frequently less of a problem with chloramination compared with chlorination. Unknown or unregulated DBPs like carcinogenic nitrosamines or iodinated disinfection byproducts, however, can form with the use of chloramines.

A 2024 study identified a disinfection byproduct (DBP) of chloramine disinfection called the chloronitramide anion.[9] It was found in all of the drinking water samples tested in the study (all of which were treated using chloramine). There are signs that the chloronitramide anion in drinking water may be toxic and present at higher concentrations than regulated disinfection byproducts.

Quick Guide to Trihalomethanes and Haloacetic Acids

Aesthetic Issues

Water chlorination impacts the taste of tap water. Chlorine can be smelled (and often tasted) at just 1 PPM.[2] Many people find the taste and smell of chlorine in their tap water to be off-putting. It’s important to remember that water utilities always ensure your tap water is safe to drink (unless otherwise specified).

Activated carbon filters, including many common pitcher filters and faucet-mounted filters, are generally effective in reducing the chlorine taste (and other taste and odor issues) in drinking water. Additionally, you can leave a glass or pitcher of water in the refrigerator for a short period of time to neutralize its odor and taste.

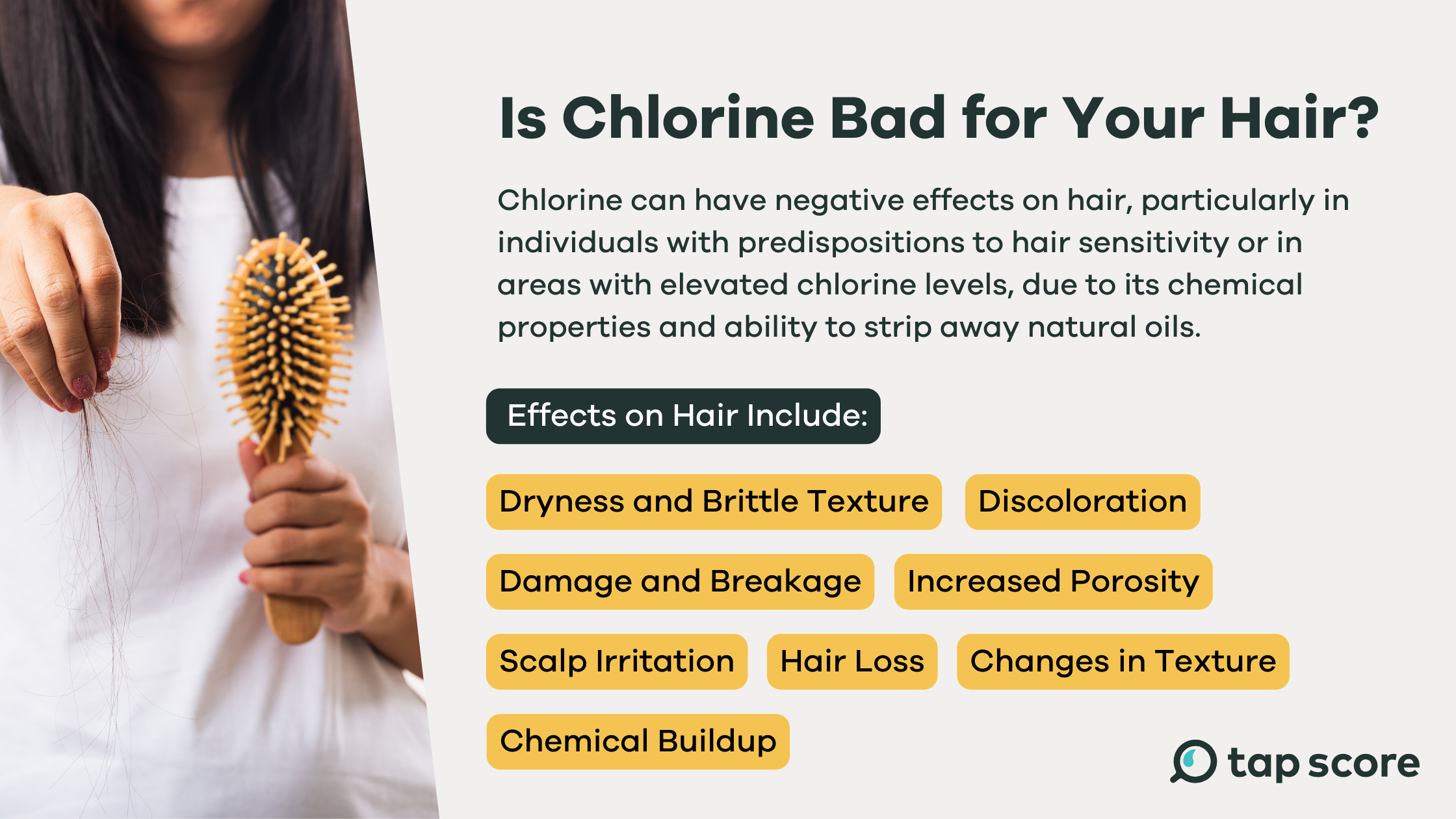

Is chlorine bad for your hair & skin?

While most people don’t notice the effects of chlorine in their drinking water, some people are highly sensitive to even low levels of chlorinated water.

Studies show showering with chlorinated water can lead to more chlorine absorption in the body than drinking it.[3] Unlike other drinking water contaminants (e.g., lead or arsenic), chlorine and related DBPs are readily absorbed through skin, and can also pose a risk if inhaled.

It’s worth noting that skin irritation from chlorine levels is predominantly a concern for swimming pool users as public utilities use reduced levels to disinfect tap water. Nevertheless, some people can be highly sensitive to chlorine.

Additionally, warm water opens up your skin pores and hair follicles, leading to greater exposure when you take a hot shower. Chlorine and its byproducts strip away the natural hair and skin oils that protect your body from over-drying.

Is Tap Water Bad for My Hair & Skin?

Chlorine, Chloramine, and the Risks of Lead Leaching

Lead (or any metal) leaching occurs when corrosive water enters an old pipeline and easily reacts with the metal pipes, creating harmful metal ions that contaminate the water.

Elemental chlorine from the chlorine compounds used in water disinfection can combine with lead to form an oxide, which acts as a passivation (protective) layer on the inside of the pipes. This passivation layer is a good thing as it protects pipes from corrosive water, helping to prevent lead leaching.

Chloramine, on the other hand, does not form a passivation layer. Compounds such as zinc orthophosphate exist to help corrosion control while using chloramine as a disinfectant by reacting with pipes to form a passivation layer.

This added step must be a part of effective chloramination in municipal water systems, otherwise chloramination could accelerate leaching in lead pipes. Utilities must keep a close eye on disinfection methods as well as their piping infrastructure to help prevent the leaching of dangerous heavy metals into taps.

Is Disinfection of Drinking Water Regulated?

Yes, common drinking water disinfectants (chlorine, chloramine, and chlorine dioxide) and their potential byproducts are regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA).[4]

- Chlorine: 4 PPM

- Chloramine: 4 PPM

- Chlorine dioxide: 0.8 PPM

Levels of free chlorine in public water supplies are typically between 0.5 and 2.0 PPM.

Additionally, while water chlorination is an effective method for disinfecting water, it's essential to strike a balance between ensuring water safety and minimizing potential risks. Exposure to too much chlorine can cause adverse health and aesthetic effects. Additionally, the formation of harmful disinfection by-products (DBPs) (as discussed above) poses health risks of their own. A handful of these compounds are also regulated.

Can I Filter My Water for Chlorine and Chloramine?

Yes, most filtration devices and water treatment systems address the aesthetic issues related to water chlorination. You’ll want to look for water filtration devices certified for NSF/ANSI Standard 42 (“certified to reduce aesthetic impurities such as chlorine and taste/odor”). (The National Sanitation Foundation, NSF, independently develops standards and conducts product testing, inspection, and certification for residential water treatment devices to better inform and protect consumers.)

Does boiling water purify chlorine from water?

Yes, boiling water will remove chlorine from your tap water. Likewise, leaving a glass or pitcher in the refrigerator overnight will remove chlorine as well. Neither boiling nor evaporation will remove chloramines, however.

On the other hand, boiling water can concentrate other contaminants that may be in your water. It can also increase your exposure to DBPs by releasing them into the air as water vapor. Unless you receive a boil advisory from your utility company (for microorganism contamination), boiling water is not the best go-to option to deal with contaminants.

Should I Test My Water for Chlorine and Chloramine at Home?

Commonly, DIY water test strips are used for owners of swimming pools and hot tubs to get an idea of chlorine levels. For drinking water, however, having a sample from your tap tested by a certified laboratory is strongly recommended—but not necessary—to understand your chlorine levels.

Chlorine and chloramine themselves are not necessarily harmful to your health, certainly not at the levels of common exposure. Instead, it’s how chlorine and chloramine interact with what’s in your water—and what your water travels through—that can be an indicator of risk levels.

Laboratory testing provides more information than just free or total chlorine levels. It provides crucial information on a wide variety of contaminants that may be in your water—including disinfection byproducts—and how they interact with your water’s unique chemistry. This can be integral to understanding whether corrosive conditions could be causing your pipes to leach harmful compounds.

Public Water Systems

As we mentioned, utilities meticulously adjust disinfection levels. Therefore testing your municipal water to get a glimpse at potential DBPs can be very helpful.

Private Well Owners

As a well owner, your water’s safety is completely in your hands—that includes disinfection. Testing your well water annually provides crucial information on the health and safety of your tap water system.

What’s the Takeaway?

Both chlorine and chloramine contain their own unique advantages and disadvantages. Regardless, disinfection byproducts remain a threat to keep in mind—and one that treatment plants work hard to combat.

- Water chlorination involves adding chlorine gas, liquid chlorine, or solid chlorine compounds to a water supply in order to kill harmful pathogens. Water treatment facilities carefully control and adjust concentrations of chlorine for proper disinfection.

- Chloramine is a combination of chlorine and ammonia. It is a longer-lasting disinfectant that results in fewer of the better understood, regulated disinfection byproducts, but it presents a greater risk when it comes to unknown and regulated disinfection byproducts, as well as increases the risk of lead and copper exposure in homes with older plumbing.

- Testing your water allows you to understand how chlorine or chloramine individually affects your water's unique chemistry

Read More

▾Quick Guide to Trihalomethanes and Haloacetic Acids

Do Water Filters Remove Haloacetic Acids?

Is Tap Water Ruining My Hair & Skin

Sources and References

▾- Water Disinfection with Chlorine and Chloramine | Public Water Systems | Drinking Water | Healthy Water | CDC

- Taste & Odor Fact Sheet | WQA

- Health Effects from Swimming Training in Chlorinated Pools and the Corresponding Metabolic Stress Pathways - PMC

- National Primary Drinking Water Regulations | US EPA

- Chloramines in Drinking Water | US EPA

- Stage 1 and Stage 2 Disinfectants and Disinfection Byproducts Rules

- BASIC INFORMATION ABOUT DRINKING WATER DISINFECTION

- WATER SYSTEMS, DISINFECTION BYPRODUCTS, AND THE USE OF MONOCHLORAMINE

- Chloronitramide anion is a decomposition product of inorganic chloramines | Science